Linux Security Module (LSM)

LSM is a framework built into the Linux kernel that provides a set of hooks—well-defined points in the kernel code—where security modules can enforce access control and other security policies. These hooks are statically integrated into the kernel, meaning that a given security module (such as SELinux, AppArmor, or Smack) is selected at build or boot time via configuration options. Once active, the LSM framework directs security-relevant decisions (like permission checks, file access, or process operations) through these hooks so that the chosen security policy is applied consistently throughout the system.

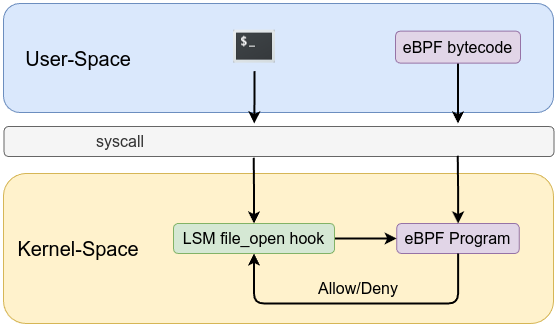

LSM with eBPF Hooks

Traditionally, LSM hooks require the security policy to be built into the kernel, and modifying policies often involves a kernel rebuild or reboot. With the rise of eBPF, it is now possible to attach eBPF programs to certain LSM hooks dynamically starting from kernel version 5.7. This modern approach allows for:

- Dynamic Policy Updates: eBPF programs can be loaded, updated, or removed at runtime without rebooting the system.

- Fine-Grained Control: LSM with eBPF can potentially provide more granular visibility and control over kernel behavior. It can monitor system calls, intercept kernel functions, and enforce policies with a level of detail that is hard to achieve with static hooks alone.

- Flexibility and Experimentation: Administrators and security professionals can quickly test and deploy new security policies, fine-tune behavior, or respond to emerging threats without lengthy kernel recompilations.

- Runtime Enforcement: eBPF programs attached to LSM hooks (using the BPF_PROG_TYPE_LSM) can inspect the kernel context and actively enforce security decisions (such as logging events or rejecting operations).

In short, while traditional LSM modules (such as SELinux) enforce security policies statically at build time, LSM with eBPF hooks introduces dynamic, runtime adaptability to kernel security. This hybrid approach leverages the robustness of the LSM framework and the operational agility of eBPF. The LSM interface triggers immediately before the kernel acts on a data structure, and at each hook point, a callback function determines whether to permit the action.

Let’s explore together LSM with eBPF. First, we need to check if BPF LSM is supported by the kernel:

cat /boot/config-$(uname -r) | grep BPF_LSM

If the output is CONFIG_BPF_LSM=y then the BPF LSM is supported. Then we check if BPF LSM is enabled:

cat /sys/kernel/security/lsm

if the output contains bpf then the module is enabled like the following:

lockdown,capability,landlock,yama,apparmor,tomoyo,bpf,ipe,ima,evm

If the output includes ndlock, lockdown, yama, integrity, and apparmor along with bpf, add GRUB_CMDLINE_LINUX="lsm=ndlock,lockdown,yama,integrity,apparmor,bpf" to the /etc/default/grub file, update GRUB using sudo update-grub2, and reboot.

The list of all LSM hooks are defined in include/linux/lsm_hook_defs.h, the following is just an example of it:

LSM_HOOK(int, 0, path_chmod, const struct path *path, umode_t mode)

LSM_HOOK(int, 0, path_chown, const struct path *path, kuid_t uid, kgid_t gid)

LSM_HOOK(int, 0, path_chroot, const struct path *path)

LSM hooks documentation which has descriptive documentation for most of LSM hooks such as:

* @path_chmod:

* Check for permission to change a mode of the file @path. The new

* mode is specified in @mode.

* @path contains the path structure of the file to change the mode.

* @mode contains the new DAC's permission, which is a bitmask of

* constants from <include/uapi/linux/stat.h>.

* Return 0 if permission is granted.

* @path_chown:

* Check for permission to change owner/group of a file or directory.

* @path contains the path structure.

* @uid contains new owner's ID.

* @gid contains new group's ID.

* Return 0 if permission is granted.

* @path_chroot:

* Check for permission to change root directory.

* @path contains the path structure.

* Return 0 if permission is granted.

Let’s explore LSM with path_mkdir LSM hook which described as the following:

* @path_mkdir:

* Check permissions to create a new directory in the existing directory

* associated with path structure @path.

* @dir contains the path structure of parent of the directory

* to be created.

* @dentry contains the dentry structure of new directory.

* @mode contains the mode of new directory.

* Return 0 if permission is granted.

path_mkdir is defined in LSM as the following:

LSM_HOOK(int, 0, path_mkdir, const struct path *dir, struct dentry *dentry, umode_t mode)

#include "vmlinux.h"

#include <bpf/bpf_core_read.h>

#include <bpf/bpf_helpers.h>

#include <bpf/bpf_tracing.h>

#define FULL_PATH_LEN 256

char _license[] SEC("license") = "GPL";

SEC("lsm/path_mkdir")

int BPF_PROG(path_mkdir, const struct path *dir, struct dentry *dentry, umode_t mode, int ret)

{

char full_path[FULL_PATH_LEN] = {};

u64 uid_gid = bpf_get_current_uid_gid();

u32 uid = (u32) uid_gid;

const char *dname = (const char *)BPF_CORE_READ(dentry, d_name.name);

bpf_path_d_path((struct path *)dir, full_path, sizeof(full_path));

bpf_printk("LSM: mkdir '%s' in directory '%s' with mode %d, UID %d\n", dname, full_path, mode, uid);

return 0;

}

struct path is data structure used by the VFS (Virtual Filesystem) layer to represent a location in the filesystem. struct path is defined in include/linux/path.h as the following

struct path {

struct vfsmount *mnt;

struct dentry *dentry;

}

struct dentry directory entry data structure which is responsible for making links between inodes and filename. struct dentry is defined in include/linux/dcache.h as the following:

struct dentry {

unsigned int d_flags;

seqcount_spinlock_t d_seq;

struct hlist_bl_node d_hash;

struct dentry *d_parent;

struct qstr d_name;

struct inode *d_inode;

unsigned char d_iname[DNAME_INLINE_LEN];

const struct dentry_operations *d_op;

struct super_block *d_sb;

unsigned long d_time;

void *d_fsdata;

struct lockref d_lockref;

union {

struct list_head d_lru;

wait_queue_head_t *d_wait;

};

struct hlist_node d_sib;

struct hlist_head d_children;

union {

struct hlist_node d_alias;

struct hlist_bl_node d_in_lookup_hash;

struct rcu_head d_rcu;

} d_u;

};

struct dentry data structure has a member struct qstr data structure that contains information about the name (a pointer to the actual character array containing the name) defined in include/linux/dcache.h as the following:

struct qstr {

union {

struct {

HASH_LEN_DECLARE;

};

u64 hash_len;

};

const unsigned char *name;

};

That’s how you extract the filename: by reading the dentry data structure, then accessing its d_name member, and finally retrieving the name member using BPF_CORE_READ macro.

const char *dname = (const char *)BPF_CORE_READ(dentry, d_name.name);

bpf_path_d_path Kernel function i used to extract the path name for the supplied path data structure defined in fs/bpf_fs_kfuncs.c in the kernel source code as the following:

__bpf_kfunc int bpf_path_d_path(struct path *path, char *buf, size_t buf__sz)

{

int len;

char *ret;

if (!buf__sz)

return -EINVAL;

ret = d_path(path, buf, buf__sz);

if (IS_ERR(ret))

return PTR_ERR(ret);

len = buf + buf__sz - ret;

memmove(buf, ret, len);

return len;

}

There is a comment in the source code very descriptive about this kernel function which says:

* bpf_path_d_path - resolve the pathname for the supplied path

* @path: path to resolve the pathname for

* @buf: buffer to return the resolved pathname in

* @buf__sz: length of the supplied buffer

*

* Resolve the pathname for the supplied *path* and store it in *buf*. This BPF

* kfunc is the safer variant of the legacy bpf_d_path() helper and should be

* used in place of bpf_d_path() whenever possible. It enforces KF_TRUSTED_ARGS

* semantics, meaning that the supplied *path* must itself hold a valid

* reference, or else the BPF program will be outright rejected by the BPF

* verifier.

*

* This BPF kfunc may only be called from BPF LSM programs.

*

* Return: A positive integer corresponding to the length of the resolved

* pathname in *buf*, including the NUL termination character. On error, a

* negative integer is returned.

bpf_get_current_uid_gid helper function to get the current UID and GID.

u64 uid_gid = bpf_get_current_uid_gid();

u32 uid = (u32) uid_gid; // the lower 32 bits are the UID

The user-space code is like the following:

#include <stdio.h>

#include <unistd.h>

#include <sys/resource.h>

#include <bpf/libbpf.h>

#include "lsm_mkdir.skel.h"

static int libbpf_print_fn(enum libbpf_print_level level, const char *format, va_list args)

{

return vfprintf(stderr, format, args);

}

int main(int argc, char **argv)

{

struct lsm_mkdir *skel;

int err;

libbpf_set_print(libbpf_print_fn);

skel = lsm_mkdir__open();

if (!skel) {

fprintf(stderr, "Failed to open BPF skeleton\n");

return 1;

}

err = lsm_mkdir__load(skel);

if (err) {

fprintf(stderr, "Failed to load and verify BPF skeleton\n");

goto cleanup;

}

err = lsm_mkdir__attach(skel);

if (err) {

fprintf(stderr, "Failed to attach BPF skeleton\n");

goto cleanup;

}

printf("Successfully started! Please run `sudo cat /sys/kernel/debug/tracing/trace_pipe` "

"to see output of the BPF programs.\n");

for (;;) {

fprintf(stderr, ".");

sleep(1);

}

cleanup:

lsm_mkdir__destroy(skel);

return -err;

}

Output:

[...] LSM: mkdir 'test1' in directory '/tmp' with mode 511, UID 1000

[...] LSM: mkdir 'test2' in directory '/tmp' with mode 511, UID 1000

eBPF LSM are classified as BPF_PROG_TYPE_LSM, sudo strace -ebpf ./loader will show similar output:

[...]

bpf(BPF_PROG_LOAD, {prog_type=BPF_PROG_TYPE_LSM, insn_cnt=68, insns=0x560837bfc0e0, license="GPL", log_level=0, log_size=0, log_buf=NULL, kern_version=KERNEL_VERSION(6, 12, 12), prog_flags=0, prog_name="path_mkdir", prog_ifindex=0, expected_attach_type=BPF_LSM_MAC, prog_btf_fd=4, func_info_rec_size=8, func_info=0x560837bfa650, func_info_cnt=1, line_info_rec_size=16, line_info=0x560837bfcfb0, line_info_cnt=11, attach_btf_id=58073, attach_prog_fd=0, fd_array=NULL}, 148) = 5

This is not all, LSM is not just about observability, LSM are made to take decisions, define controls and enforce them. Let’s explore another example which its main objective to block opining /etc/passwd file.

#include "vmlinux.h"

#include <errno.h>

#include <bpf/bpf_core_read.h>

#include <bpf/bpf_helpers.h>

#include <bpf/bpf_tracing.h>

#define FULL_PATH_LEN 256

char _license[] SEC("license") = "GPL";

SEC("lsm/file_open")

int BPF_PROG(file_open, struct file *file)

{

char full_path[FULL_PATH_LEN] = {};

int ret;

const char target[] = "/etc/passwd";

int i;

ret = bpf_path_d_path(&file->f_path, full_path, sizeof(full_path));

if (ret < 0)

return 0;

for (i = 0; i < sizeof(target) - 1; i++) {

if (full_path[i] != target[i])

break;

}

if (i == sizeof(target) - 1) {

bpf_printk("Blocking open of: %s\n", full_path);

return -EPERM;

}

return 0;

}

struct file data structure represents an instance of an open file or device within a process defined in include/linux/fs.h header file in the kernel source code as the following:

struct file {

atomic_long_t f_count;

spinlock_t f_lock;

fmode_t f_mode;

const struct file_operations *f_op;

struct address_space *f_mapping;

void *private_data;

struct inode *f_inode;

unsigned int f_flags;

unsigned int f_iocb_flags;

const struct cred *f_cred;

struct path f_path;

union {

struct mutex f_pos_lock;

u64 f_pipe;

};

loff_t f_pos;

#ifdef CONFIG_SECURITY

void *f_security;

#endif

struct fown_struct *f_owner;

errseq_t f_wb_err;

errseq_t f_sb_err;

#ifdef CONFIG_EPOLL

struct hlist_head *f_ep;

#endif

union {

struct callback_head f_task_work;

struct llist_node f_llist;

struct file_ra_state f_ra;

freeptr_t f_freeptr;

};

struct file members are described as the following:

* struct file - Represents a file

* @f_count: reference count

* @f_lock: Protects f_ep, f_flags. Must not be taken from IRQ context.

* @f_mode: FMODE_* flags often used in hotpaths

* @f_op: file operations

* @f_mapping: Contents of a cacheable, mappable object.

* @private_data: filesystem or driver specific data

* @f_inode: cached inode

* @f_flags: file flags

* @f_iocb_flags: iocb flags

* @f_cred: stashed credentials of creator/opener

* @f_path: path of the file

* @f_pos_lock: lock protecting file position

* @f_pipe: specific to pipes

* @f_pos: file position

* @f_security: LSM security context of this file

* @f_owner: file owner

* @f_wb_err: writeback error

* @f_sb_err: per sb writeback errors

* @f_ep: link of all epoll hooks for this file

* @f_task_work: task work entry point

* @f_llist: work queue entrypoint

* @f_ra: file's readahead state

* @f_freeptr: Pointer used by SLAB_TYPESAFE_BY_RCU file cache (don't touch.)

Output when opening /etc/passwd shows the following:

cat-1673 [003] ...11 262.949842: bpf_trace_printk: Blocking open of: /etc/passwd

The code can also work based on comparing the inode rather than the filename. The following example uses a hard-coded inode value for demonstration purposes only.

Note

An inode (short for “index node”) a unique inode number is assigned to Each file or directory in a filesystem. When a file is accessed, the system uses the inode to locate and retrieve its metadata and content. Inode does not store the file’s name.Note

Hard-coding an inode number in your code is not suitable for portability. Inode numbers are specific to a particular filesystem and can change across different systems. This means that relying on a fixed inode number may lead to unexpected behavior in different environments.#include "vmlinux.h"

#include <errno.h>

#include <bpf/bpf_core_read.h>

#include <bpf/bpf_helpers.h>

#include <bpf/bpf_tracing.h>

#define TARGET_INODE 788319

char _license[] SEC("license") = "GPL";

SEC("lsm/file_open")

int BPF_PROG(file_open, struct file *file)

{

u64 ino = BPF_CORE_READ(file, f_inode, i_ino);

if (ino == TARGET_INODE) {

bpf_printk("Blocking open: inode %llu matched TARGET_INO\n", ino);

return -EPERM;

}

return 0;

}

First we need to obtain /etc/passwd inode using ls-i /etc/passwd:

788319 /etc/passwd

Then you use that number in your code to check against the file’s inode. Let’s see another example for socket. socket_create described in the source code as the following:

* @socket_create:

* Check permissions prior to creating a new socket.

* @family contains the requested protocol family.

* @type contains the requested communications type.

* @protocol contains the requested protocol.

* @kern set to 1 if a kernel socket.

* Return 0 if permission is granted.

socket_create LSM hook look like this in the source code also:

LSM_HOOK(int, 0, socket_create, int family, int type, int protocol, int kern)

Let’s see how to prevent UID 1000 from creating a new socket:

#include "vmlinux.h"

#include <errno.h>

#include <bpf/bpf_helpers.h>

#include <bpf/bpf_tracing.h>

char _license[] SEC("license") = "GPL";

SEC("lsm/socket_create")

int BPF_PROG(socket_create, int family, int type, int protocol, int kern)

{

u64 uid_gid = bpf_get_current_uid_gid();

u32 uid = (u32) uid_gid;

if (uid == 1000) {

bpf_printk("Blocking socket_create for uid %d, family %d, type %d, protocol %d\n",

uid, family, type, protocol);

return -EPERM;

}

return 0;

}

When a process running as UID 1000 (for example, when a user attempts to run ping or ssh) tries to create a new socket, the LSM hook for socket creation is triggered. The eBPF program intercepts the system call and uses bpf_get_current_uid_gid() to obtain the current UID. If the UID is 1000, the program returns -EPERM (which means “Operation not permitted”). This return value causes the socket creation to fail.

ping-2197 [...] Blocking socket_create for uid 1000, family 2, type 2, protocol 1

ssh-2198 [...] Blocking socket_create for uid 1000, family 2, type 1, protocol 6

Of course—you can fine-tune your policy based on the arguments passed to the hook. For example, if you only want to block socket creation for TCP (protocol number 6), you can do something like this:

if (protocol == 6) {

return -EPERM;

}

This means that only when the protocol equals 6 (TCP) will the socket creation be blocked, while other protocols will be allowed. Socket family is defined in include/linux/socket.h, while socket type is defined in include/linux/net.h and socket protocol is defined in include/uapi/linux/in.h.

I strongly recommend exploring more LSM hooks on your own and consulting the documentation—you’ll quickly see that working with them is not hard at all. Next, we will see Landlock which allows a process to restrict its own privileges in unprivileged manner or process sandbox.